Sink hole appears in Russia, measuring in at 164 feet across. Read the Popular Mechanics article for more.

Sink hole appears in Russia, measuring in at 164 feet across. Read the Popular Mechanics article for more.

Several months ago I left Alaska returning to the lower 48. I flew through Seattle, and the plane was empty. The airport was empty. The city was empty. It's been surreal, living in this era of ghost towns, where rather than sundown, it's the closeness that people fear. I can take a walk, and people will cross the street rather than walk close by. I find myself holding my breath as I come across people, whether grocery shopping or getting the mail. Ed Buryn once wrote, "If you view the world as a predominantly hostile place, it will be." And while in past travels that would be true, right now it's more a matter of uncertainty. No one knows. We all think, and hope, and wait. But the certainty has been escaping us. I don't know when travel will be possible, and when meeting with people in celebration of life will again be safe. But I do know that, no matter when it gets here, it can't be soon enough.

One year ago, I was just back in the lower 48. Now I’m back again from Alaska, only several weeks removed.

Last year, after my visit, I knew that I wanted to return. I’m glad that I was able to. Now being back this time, it’s like the world fundamentally shifted.

I think it feels like that for most people right now. I, like many, are left wondering: when will it be back to normal?

Apparently, some blog posts have evaporated. While I was traveling and setting up posts for the trip, some scheduled items didn’t appear to post.

Sorry about that.

Anyway, new updates to follow, including some adventures back in Atlanta!

On walking around through various parks and city streets, I notice the importance of taking one’s time.

We’re often consumed by the need to be connected and now, maybe more so than ever, our connections are only possible through devices.

When you take the time to travel slowly, to linger, to be idle (while socially distant, of course), you have the opportunity to see things you’d otherwise miss. You hear the birdsong. See the leaves billow in the wind. Branches swaying.

There’s no one right way to travel the world. But there are things that are missed when moving too quickly.

Well, damn, I don’t really have much to say about this past week. Left Alaska, and am taking a roundabout journey through the country. Had to fly to get from Ketchikan to the lower 48, and rather than risk quarantine with family, where someone I know could come in contact with something I may have contracted on the plane, it was better to take my time.

I haven’t seen much. Some snowy mountains outside of Colorado, and some rolling hills. I would have liked to have spent more time in Arizona. It seemed nice passing through.

Not sure what I’ll see or do over the next three weeks, but I’m hoping I’ll have some interesting updates… maybe by next week.

For the first time in my history of air travel, the airports looked empty. The flights were sparsely peopled, and I’d think there were more employees than travelers.

I, like most everyone else, am curious to see the new world. The world of travel, and work, and leisure. When the world reopens, sometime in the future, it’ll be greatly interesting.

All about Ketchikan, Volume 5.

The Tongass National Forest:

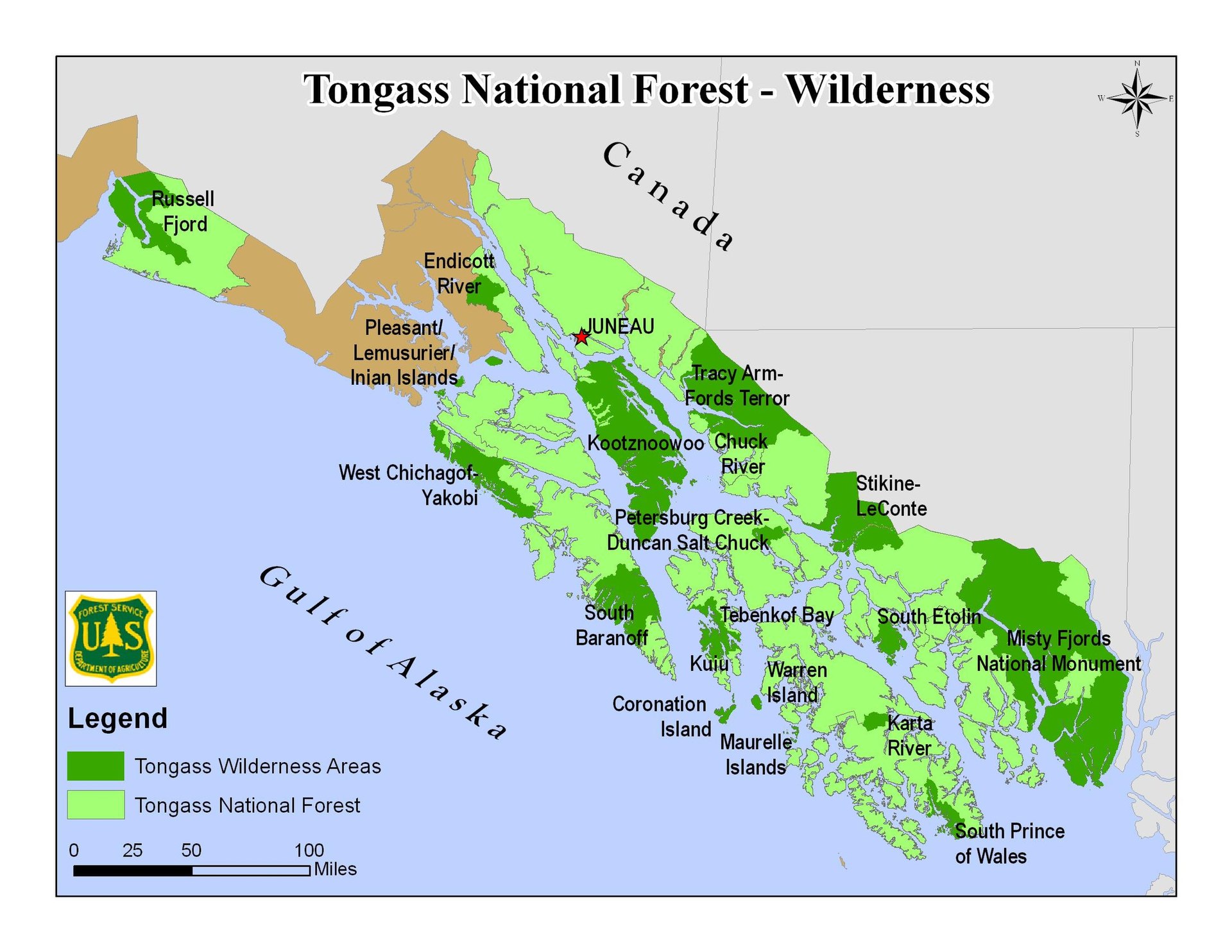

Tongass is the largest National Forest in the US and covers most of the Southeast of Alaska. Seventeen million acres, to be nearly exact.

The Tongass National Forest stretches about 500 miles along the SE Alaska coast covering an area equal in size to Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. It was designated a national forest on September 10, 1907, by proclamation of the President, Teddy Roosevelt.

Tongass is the point of some controversy recently, in the question of whether to allow logging in some of its areas. Today it is home to two national monuments (Misty Fjords and Admiralty Island) and nineteen designated wilderness areas. Which is part of a larger question of ecology vs. economy: how do you decide what’s of value?

Environmentalist (and huge Alaska fan) John Muir noted as he watched federally protected lands across the U.S. come under threat, “Nothing dollarable is safe.” And that is a conundrum that has faced man since the industrial age. What portion of land needs be preserved and what should be developed?

Sitting here, in Southeast Alaska, I’m glad there is still wilderness outside the door. In this country of ours. People from around the world come here in hoards to see Wild Alaska. Not this summer, maybe. But other summers, those in the past. And next summer, I estimate the largest tourist season yet here.

All about Ketchikan, Volume 4.

There are three groups of native people who live in this area, in and around Ketchikan, Metlakatla, and on several other islands here in the Alexander Archipelago.

“The Tsimshian were relatively late arrivals to Southeast Alaska. For thousands of years, the islands of the Alexander Archipelago had been primarily the territory of the Tlingit [prounounced clink-it]. (A third group, the Haida, arrived from the south in the eighteenth century. … Tlingit society at the start of the nineteenth century was made up of approximately sixteen tribes, called kwaan.” – Mark Adams, A Tip of the Iceberg.

“The Tlingit, originally fourteen tribes, spoke a language related to the Athabascan Indians of the interior and occupies the coast of Alaska from Yakutat Bay down to the Prince of Wales Island. Ther were pushing the Eskimo off Kayak Island in the beginning of European contacts and had begun to enter the Copper River.

The Haida, who spoke a similar language, yet one which differed somewhat from that of the Tlingit, lived on the coastal areas of the Queen Charlotte Island and the southern part of the Prince of Wales Island in Alaska.

The Tsimshian lives on the mainland from the Nass to the Skeena River and down to the area which is the modern city of Prince Rupert.” – H.R. Hays, Children of the Raven

These are the three native nations of Southeast Alaska. Two others – the Inuit, to the North, and the Aleuts, to the West – call Alaska home. The common belief is that native populations of Alaska (and the rest of the Americas) arrived across a landbridge.

“The easiest way to get here is on foot. The Bering Land Bridge has been the longstanding theory because that’s the clearest connection between Asia and North America, up in the Arctic, and it only appears when ice is locked up on land and sea levels drop. It’s the only place where you could walk from one side to the other.” – National Geographic

All about Ketchikan, Volume 3.

Alaska, like much of the Country, has pretty much shut down. Bars, restaurants, the company I was working for. However, I’m fortunate to have a number of trails to explore within walking distance.

Rainbird Trail: Scenic views and a hilly wooded path, this two-and-a-half-mile walk provides a look at the Tongass Narrows and Gravina and Pennock Islands. While moving through the forest, there is a selection of spruce, cedar, hemlock, and pine trees to observe in their tree-fulness.

Deer Mountain Trail: A significantly more strenuous hike than Rainbird, and currently covered in snow at an elevation of about one mile from the base, it only went part of the way up. Deer Mountain is described as “Ketchikan’s iconic and idyllic backdrop.”

Several other locations are within driving distance (only some 30 miles of highway move up the Western coast of Revilla Island), and these include Carlanna Lake Trail, Ward Lake and Perseverance Lake Trail, and the Coast Guard Beach Trail.

I only briefly headed down to Ward Lake, but anticipate further hiking over the weekend. The weather has turned sunny, while still hovering between thirty and forty degrees Fahrenheit.